Lori Wallace sits on a sofa together with her 11-year-old son and his new pet snake. It burrows underneath his armpit, as if afraid. Wallace is bound it’s not.

“If he was terrified, he would be balled up,” Wallace stated. “See, that is why they are called ball pythons. When they are scared, they turn into a little ball.”

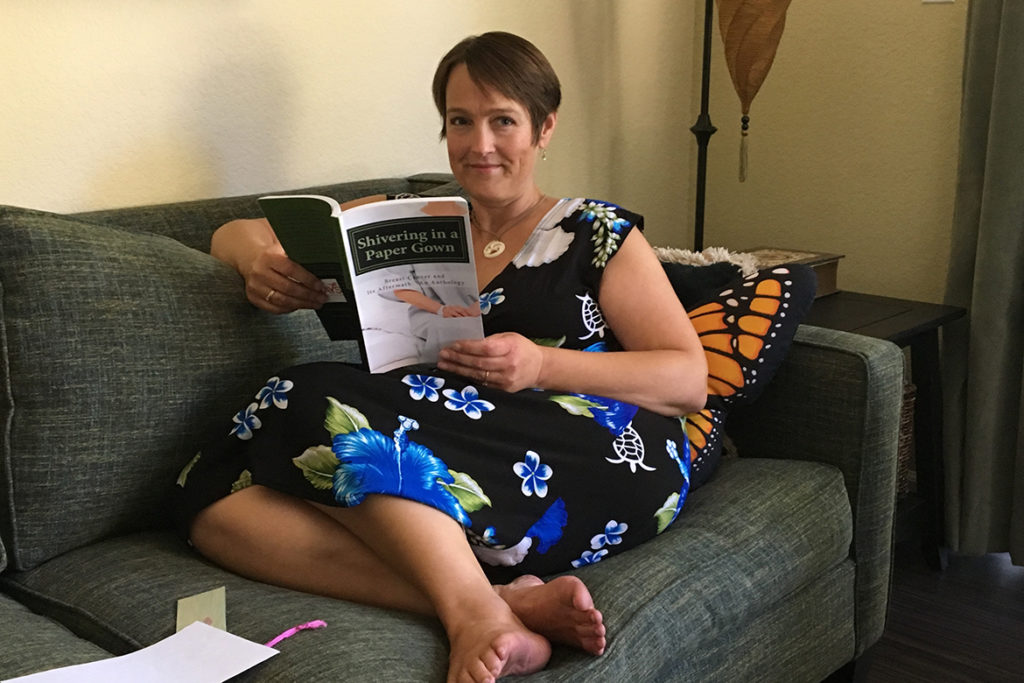

Wallace is dying of breast most cancers, however a stranger wouldn’t know. She has a pixie haircut and a heat tan. She is vibrant and chatty and appears you proper within the eyes when she talks. Wallace doesn’t draw back from what is going on to her. She exhibits me her cracked ft. They bleed from the chemotherapy capsules she takes.

As Wallace’s most cancers has progressed over the previous seven years, she has turn into extra vital of what she sees as extreme positivity in well being care advertising and marketing. It’s in all places: TV advertisements, radio commercials, billboards. The ads characteristic pleased, healed sufferers and inform tales of miraculous recoveries. The messages are optimistic, about folks beating steep odds. The advertisements unfold false hope, Wallace stated, and for a affected person like her, they’re a slap within the face.

This story is a part of a partnership that features KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News. It will be republished without spending a dime. (details)

A few many years in the past, hospitals and clinics didn’t promote a lot to prospects. Now, they’re spending increasingly more annually on advertising and marketing, in keeping with college professors who research promoting.

Wallace, who lives in San Jose, Calif., stated she was once a hopeful individual, somebody who believed you can battle by any misfortune. Then she was identified with breast most cancers at 39. Her son was four on the time. She couldn’t consider it.

She is now in her fifth spherical of chemotherapy and it makes her mind foggy, she stated. Her stage four most cancers has unfold all through her physique. It’s going to kill her, she stated.

“The median survival of a woman with metastatic breast cancer is 33 months,” Wallace stated. “My 33 months would have been Dec. 6 last year. So I am on bonus time right now.”

Wallace pulled up an advert on her laptop from UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, in San Francisco. An announcer intones, “Amid a thousand maybes and a million nos, we believe in the profound and unstoppable power of yes.”

There is the same form of optimism on the coronary heart of lots of the advert campaigns by well being care suppliers — with slogans like “Thrive” and “Smile Out.” Wallace stated the subtext of the advertisements is that individuals like her — who get sick and can die — perhaps simply aren’t being constructive sufficient.

“I didn’t say ‘yes’ to cancer,” Wallace stated. “I have tried everything I can. I have done clinical trials. I have said ‘yes’ to every possible treatment. And the cancer doesn’t care.”

Karuna Jaggar is government director of Breast Cancer Action. She stated well being care suppliers are following within the footsteps of different corporations.

“It’s the basics of marketing,” Jaggar stated. “In order to sell products or services, you have to sell hope.”

She stated well being care advertisers are adopting the form of optimistic messaging that basically started in pressure with the pink ribbons and rosy depictions of breast most cancers.

“Thirty years ago, breast cancer was the poster child of positive thinking,” Jaggar stated. “‘Look good, feel better, don’t let breast cancer get you down. Fight strong and be cheerful while you do it.’”

Back then, well being care suppliers marketed to physicians greater than customers. The advertisements have been drier, extra factual, stated Guy David, an economist and professor of well being care administration on the University of Pennsylvania.

“When the ads are more consumer-facing as opposed to professional-facing, the content tends to be more passionate,” David stated.

The hospital advertisements Wallace objects to tug at feelings, identical to different promoting that’s attempting to win over customers. With growing well being care prices and decisions, sufferers are buying round for care. These days hospitals need to promote themselves, stated Tim Calkins, a professor of selling at Northwestern University.

“Right now in health care, if you don’t have some leverage, if you don’t have a brand people care about, if you don’t have a reason for people to pick you over competitors — well, then you are in a really tough spot,” he stated.

Hospitals are spending greater than ever on promoting, he stated, and, as with different merchandise, that promoting is crammed with a number of guarantees. He famous that you simply don’t see the identical guarantees within the pharmaceutical business. Their advertisements are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration, which is why they need to checklist unintended effects and present scientific backing for his or her claims.

“Hospitals aren’t held to any of those [FDA] standards at all,” Calkins stated. “So a hospital can go out and say, ‘This is where miracles happen. And here’s Joe. Joe was about to die. And now Joe is going to live forever.’”

Lori Wallace will not be going to dwell without end. Before most cancers, she stated, she would have been interested in the messages of hope. But now, she craves realism — acceptance of each the world’s magnificence and its harshness. She wrote an essay about that for the ladies in her breast most cancers assist group.

The essay is titled “F*** Silver Linings and Pink Ribbons.” Wallace reads the entire piece aloud, from begin to end, sitting at her kitchen desk. Her son is close by along with his pet snake.

Toward the center of the essay, Wallace writes, “My ovaries are gone, and without them my skin is aging at hyperspeed. I have hot flashes and cold flashes. My bones ache. My libido is shot and my vagina is a desert.” The essay is open, humorous and unflinching, identical to Wallace.

She reads the ultimate paragraph: “I will try to be thankful for every laugh, hug and kiss, and other things, too. That is, if my chemo-brain allows me to remember.”

“That’s what I wrote,” Wallace stated. “That’s what I wrote. Brutal honesty.”

This story is a part of a partnership that features KQED, NPR and Kaiser Health News.