This story additionally ran on NBC News. This story will be republished without spending a dime (details).

“It would feel like murder to pull her life support,” a younger girl tells the physician.

The girl sits by a hospital mattress the place her mom, Selena, lies unresponsive, hooked as much as a respiration tube. The daughter has already made one try to save lots of her mom’s life; she pulled Selena out of the automobile and carried out CPR when her coronary heart stopped en path to the hospital — an expertise she calls “beyond terrifying.”

Now the physician tells the household Selena won’t ever get up in a significant approach. But the daughter says she will’t let her mom go: “I’m always looking for another miracle.”

The scene, captured within the documentary “Extremis,” passed off in a hospital’s intensive care unit in Oakland, Calif.

Three thousand miles away, at Boston’s Bethel AME Church one latest fall night, the Rev. Gloria White-Hammond watched the movie with a gaggle of ladies from her predominantly black congregation. As they gathered round an extended desk within the church’s youth middle at 7 p.m., White-Hammond supplied oranges and chocolate chip cookies — and a warning that the movie may be very exhausting to look at.

White-Hammond, an brisk 67-year-old activist and minister who additionally teaches at Harvard Divinity School, is accustomed to broaching tough topics. She typically speaks out about being sexually abused by her father throughout childhood — an expertise that motivated her to work with survivors of sexual violence in Sudan. Now, she’s utilizing her uncommon credentials as a pastor — and a pediatrician — to tackle a brand new topic: demise.

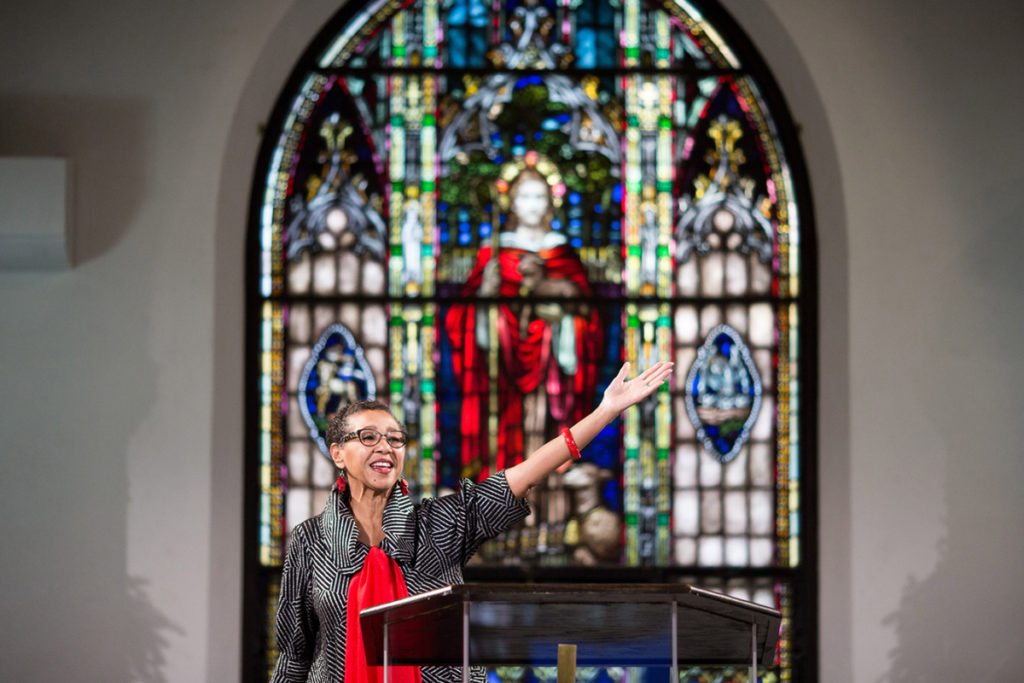

Pastor Gloria White-Hammond speaks with parishioners after a Sunday service at Boston’s Bethel AME Church. White-Hammond needs to get all 600 congregants to put in writing down their end-of-life needs and focus on them with their households. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)

As the movie ended, White-Hammond and her congregants sat quietly as letters on the display revealed Selena’s destiny: The household had Selena surgically connected to a respiration machine. She lived that approach, drifting out and in of consciousness, for almost six months.

White-Hammond broke the silence with a prayer.

“We know Selena,” she stated, talking metaphorically. “Her brothers are our brothers.”

Like Selena, the general public within the room have been black ladies. They are grappling with the query: If they find yourself like Selena, what would they need their households to do?

“God, guide us and direct us,” stated White-Hammond as heads bowed. After they die, she stated, her parishioners might even see the face of Jesus, and “sit at his feet and be blessed.”

But first, they’ve work to do.

Pastor Gloria White-Hammond and her husband and co-pastor, Ray Hammond, stand throughout a Sunday service at Bethel AME Church on Dec. three, 2017, in Boston. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)

White-Hammond is set to get all of her 600 congregants to put in writing down their end-of-life medical needs and focus on them with their docs and households.

White-Hammond handled sufferers till about seven years in the past, and her husband and co-pastor, Ray Hammond, is a health care provider, too. But when a corporation referred to as The Conversation Project approached her a number of years in the past about main death-and-dying workshops along with her congregation, she found she hadn’t deliberate for her personal demise or critical sickness.

“I didn’t have my own documents” outlining medical needs, she stated. “I was kind of embarrassed.”

Nationwide, solely a 3rd of Americans have documented their end-of-life needs, in line with a recent poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation. For black adults 65 or older, charges are a lot decrease: Only 19 p.c have documented their end-of-life needs, in contrast with 65 p.c of whites. Older black adults are half as possible as whites to have named somebody to make medical selections on their behalf in the event that they grew to become incapacitated, the ballot discovered. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially impartial program of the inspiration.)

Another KFF poll discovered that blacks are extra possible than whites to say that residing so long as potential is “extremely important,” and that the U.S. medical system locations too little emphasis on extending life.

As a part of the dialogue at Bethel AME, White-Hammond requested attendees to look via the “Five Wishes” end-of-life planning doc. At month-to-month workshops, White-Hammond has launched over 100 parishioners to the doc over the previous two years. She stated folks typically get caught when filling out the second want, which asks whether or not they need life help in sure grim situations that they might not be conversant in, reminiscent of everlasting mind injury.

White-Hammond screened “Extremis” for instance what ventilators and feeding tubes are actually like — and what it’s like for households to make selections with out express directions. The documentary, which lasts an intense 24 minutes, provoked a robust response.

Pastor Gloria White-Hammond distributes Holy Communion throughout a Sunday service at Bethel AME Church in Boston. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)

Pastor Gloria White-Hammond has launched over 100 of her parishioners to the “Five Wishes” end-of-life planning doc at month-to-month workshops over the previous two years. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)

Janine Hackshaw, a 35-year-old black immigrant from Trinidad who works in microfinance, informed the group she felt anger towards one ICU physician within the movie. She felt the physician was dashing a household to make a life-or-death choice about whether or not to place their beloved one on a ventilator.

“Why is she rushing?” Hackshaw requested. “Do you need the machine for something else?”

Mistrust of the medical institution is one main cause black Americans are much less prone to write down their end-of-life needs, and extra reluctant to finish life help, White-Hammond later stated. That distrust stems partly from historic racism, together with segregated hospitals, pressured sterilization of black ladies and the notorious, government-led Tuskegee syphilis experiment that denied efficient therapy to black males.

The distrust persists at this time as “race becomes more tense” across the country, and as folks proceed to expertise disparities, White-Hammond stated. Like some other black church leaders throughout the nation who’re making an attempt to vary perceptions round hospice, White-Hammond believes cultural change can begin at church.

“We’re capitalizing on our credibility as an institution of faith” to drive conversations round end-of-life care, she stated. The aim, she stated, is to make these discussions “part of the culture.”

Another impediment, White-Hammond stated, is that folks don’t need to speak about demise.

Rhona Julien, one other parishioner who hails from Trinidad, stated she regrets avoiding the dialogue along with her mom earlier than she died three years in the past. When her mom began to speak about dying, Julien would change the topic.

“I never wanted to deal with it,” she stated.

Pastor Gloria White-Hammond speaks with parishioner Rainelle Walker White throughout a Sunday service. Only 19 p.c of blacks 65 or older have documented their end-of-life needs, in contrast with 65 p.c of whites. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)Pastor Gloria White-Hammond speaks with parishioner Joyce Sackey Acheampong. Mistrust of the medical institution is one main cause black Americans are much less prone to write down their end-of-life needs, and extra reluctant to finish life help, White-Hammond says. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)Pastor Gloria White-Hammond prays at Boston’s Bethel AME Church. Before she set out on a mission to assist parishioners doc their last needs, she was embarrassed that she herself hadn’t ready her personal advance directive. (Kayana Szymczak for KHN)

But she stated she discovered lots from her mom’s demise, together with the strain households might create to maintain an individual alive. Julien, a 58-year-old environmental scientist, was the only caretaker for her mom, who had pulmonary fibrosis. At the very finish, Julien stated, her siblings wished to place their mom on a ventilator, to maintain her alive lengthy sufficient in order that they may fly from Trinidad to say goodbye. Julien refused.

“She’s not going to be connected to a machine to keep her alive for other people’s benefit,” Julien recalled considering.

“Nobody should be hooked up to this and that, like Frankenstein,” she stated.

A 23-year-old Haitian-American girl within the group stated she has not been comfy talking as much as her household about her grandmother’s care. (She declined to provide her title, for concern of upsetting her household.)

She described her grandmother, who moved to the U.S. from Haiti, as an impartial, strong-minded girl who would recurrently stroll an hour to church as a substitute of taking a bus. She raised three youngsters on her personal and made a life within the U.S., though she didn’t communicate English, couldn’t learn and had no formal schooling.

Her grandmother was so ready for demise that she had a drawer in her room with garments that she deliberate to put on at her funeral — a sublime white swimsuit and white, wide-brimmed hat. She would verify the drawer each couple of weeks.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

But when the grandmother had a stroke a few years in the past in Randolph, Mass., docs requested if she ought to be saved on feeding tubes or supplied solely consolation care. The household selected feeding tubes. The grandmother, who’s 85 and can’t stroll or speak, has been residing in a mattress ever since.

The younger girl stated she feels pissed off that her household didn’t prioritize what her grandmother would need.

“We were hoping for a miracle,” she stated. But she knew her grandmother “wouldn’t have decided to live a life where she would be bound to a bed.”

Dr. Alice Coombs, one in all three black feminine docs taking part within the night’s dialogue, turned to the younger girl and gently steered that she communicate up on her grandmother’s behalf.

“I took it as a challenge,” the younger girl later stated, “to talk about this topic.”

Julien stated she was initially reluctant to speak to her personal youngsters about her end-of-life needs — “Are you jinxing yourself?” she puzzled — however she efficiently broached the topic as a part of homework for the workshop.

After watching the movie “Extremis,” she stated, she felt motivated to take the subsequent step: “I’m going to fill out these forms!”

As the dialogue ended, White-Hammond prayed to God for assist filling out these end-of-life types. “Put the fire under us,” she requested, so the duty doesn’t languish “on the to-do list.”

KHN’s protection of those subjects is supported by Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and The SCAN Foundation

Melissa Bailey: mbailey@kff.org”>mbailey@kff.org, @mmbaily

Related Topics Aging Public Health Disparities End Of Life src=”http://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js” charset=”utf-Eight”>