From her laboratory within the far western reaches of Montana, Elizabeth Fischer is attempting to assist individuals see what they’re up towards in COVID-19.

Over the previous three many years, Fischer, 58, and her crew on the Rocky Mountain Laboratories, a part of the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, have captured and created among the extra dramatic pictures of the world’s most harmful pathogens.

“I like to get images out there to try to convey that this is an entity, to try to demystify it, so this is something more tangible for people,” stated Fischer, one of many nation’s main electron microscopists.

Now, as her renderings of the coronavirus flash throughout screens worldwide, she stated: “You often hear people call it the invisible enemy. It’s trying to put that face out there.” Working in one of many nation’s 13 “Biosafety Level 4” labs — these geared up to securely deal with probably the most harmful pathogens — Fischer and her crew visualize the world’s deadliest plagues from Ebola to HIV, salmonella to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

The breathtaking pictures permit individuals to see a virus as elaborate organic constructions with weaknesses that may be exploited, yielding clues for researchers about develop remedies and vaccines.

“If there is a disease, we have seen it,” she stated.

Originally from Evergreen, Colorado, Fischer accomplished a level in biology on the University of Colorado-Boulder and contemplated going to medical college, earlier than deciding as a substitute to affix the Peace Corps. She taught math and science for 2 years in Liberia, after which took time to journey by way of East Africa and Asia, together with a trek into the Himalayas.

Returning to Colorado, she immersed herself within the out of doors world she beloved. She labored as a rafting information on the Arkansas River for a number of summers, and as a youngsters’s ski teacher on the Monarch Mountain ski resort throughout the winters.

She later enrolled in graduate college, pondering she would possibly train biology. But when she took programs in electron microscopy, she was hooked.

It appealed to her sense of unique journey. “You’re looking at a world that most people don’t get to see,” she stated. She switched gears and accomplished a grasp’s diploma in biology.

Upon commencement, she despatched her résumé to a nationwide microscopy job placement workplace and shortly acquired a name from Rocky Mountain Laboratories. In 1994, she moved along with her household to Hamilton, a metropolis of fewer than 5,000 individuals about 50 miles south of Missoula, then labored her approach as much as turn into chief of the lab’s microscopy unit.

Some of the extra gorgeous pictures of the coronavirus — about 10,000 instances smaller than the width of a human hair — have come from Fischer’s microscope.

Elizabeth Fischer makes use of an electron microscope to seize pictures of the coronavirus, which is about 10,000 instances smaller than the width of a human hair.(Courtesy of Elizabeth Fischer)

“I like to get images out there to try to convey that this is an entity, to try to demystify it, so this is something more tangible for people,” Fischer says.(Courtesy of Elizabeth Fischer)

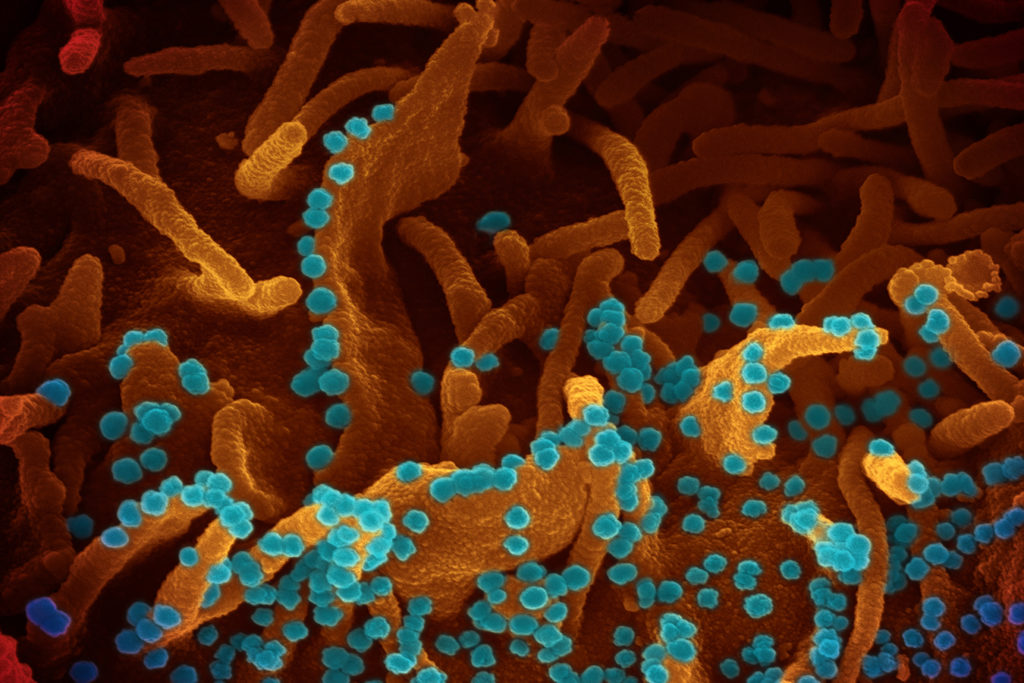

One is Fischer’s photograph of viral particles being launched from a dying cell contaminated with the virus.

As NIH Director Dr. Francis Collins lately highlighted in his blog, the photograph exhibits the orange-brown folds and protrusion on the floor of a primate’s kidney cell contaminated with SARS-CoV-2. The dozens of small, blue spheres rising from the floor are the virus particles themselves. (The pictures produced by the electron microscopes are black-and-white, so Fischer arms them over to visible artists who colorize the picture to assist establish totally different components of the cell and to tell apart the virus from its host.)

“This image gives us a window into how devastatingly effective SARS-CoV-2 appears to be at co-opting a host’s cellular machinery,” Collins wrote. “Just one infected cell is capable of releasing thousands of new virus particles that can, in turn, be transmitted to others.”

Scientists like Fischer have used electron microscopes to uncover the unseen world of viruses and micro organism courting to the 1930s. In the previous 20 years, nevertheless, new applied sciences have unleashed a decision revolution, permitting researchers to see right down to the near-atomic degree. Microscopists have give you higher methods to arrange samples for viewing and have written subtle software program packages to sharpen pictures.

Through her lab, Fischer receives samples from all around the world, and was despatched viral materials in early February from one of many first U.S. sufferers to be contaminated with the novel coronavirus. Often, her samples come from vials which were saved in a freezer for many years, or from cultures routinely grown in a lab. “It’s very sobering when you know it came from a human patient.”

In 2014, Elizabeth Fischer acquired a pattern of Ebola from a 2-year-old woman in Mali. The cell border and nucleus form resemble the form of Africa.

For instance, in 2014, a sister lab in Mali despatched over an Ebola pattern from a 2-year-old woman who had lived in Guinea when her mom died of the illness. Her grandmother traveled from Mali to attend the funeral, which concerned touching and bathing the physique, and to take the woman dwelling along with her. Both acquired contaminated and introduced the virus again with them as they returned to Mali by public transportation. They each died.

“This one particular cell, it looked like the continent of Africa,” Fischer recalled. “It was a very powerful moment. You see that virus growing in there, it takes you back around to not only the lab work we do, but that there’s an impact on human health.”

Despite the lethal nature of the viruses, she nonetheless appreciates the “beautiful symmetry in many of them,” she stated: “They’re very elegant, and they’re not malicious in and of themselves. They’re just doing what they do.”