One of the targets President Donald Trump introduced in his State of the Union deal with was to cease the unfold of HIV within the U.S. inside 10 years.

In addition to sending more money to 48 primarily city counties, Washington, D.C., and San Juan, Puerto Rico, Trump’s plan targets seven states the place rural transmission of HIV is very excessive.

Health officers and docs treating sufferers with HIV in these states say any additional funding can be welcome. But they are saying methods that work in progressive cities like Seattle gained’t essentially work in rural areas of Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, Missouri, Oklahoma and South Carolina.

Stigma round HIV and AIDS and round being homosexual runs deep in components of Oklahoma, stated Dr. Michelle Salvaggio, medical director of the Infectious Diseases Institute on the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center in Oklahoma City. The institute is one in every of two federally funded HIV clinics in Oklahoma; the opposite is in Tulsa, the state’s second-largest metropolis.

A Long Drive For Anonymity

Salvaggio’s clinic has six examination rooms the place she sees sufferers, lots of whom drive hours for therapy. The clinic used to make use of a case supervisor in rural Woodward County, a bit of greater than two hours’ drive northwest of Oklahoma City.

But Salvaggio stated that ended up being a waste of cash. “We had to let that position go, because nobody would go see her,” Salvaggio stated. “Because they didn’t want to be seen walking into the HIV case manager’s office in that tiny town — that can only mean one thing.”

In Oklahoma, as in a lot of the U.S., black gay and bisexual men have the highest risk of HIV an infection. Other teams with elevated threat in Oklahoma embody Latinos, heterosexual ladies and Native Americans.

Salvaggio applauds the purpose of ending HIV transmissions inside 10 years however stated she doesn’t suppose it’s possible in Oklahoma. The plan fails to acknowledge the actual methods totally different populations expertise the epidemic, she stated.

Native Americans in Oklahoma, for instance, can’t depend on the anonymity of a giant well being clinic.

“When they go into an Indian Health Service clinic, it is possible that they will see their cousin behind the desk, and their cousin’s brother-in-law working in medical records, and their niece’s boyfriend working in the pharmacy,” Salvaggio stated.

Even if Native Americans have entry to HIV care on the clinic, she stated, “they are literally in fear of being outed.”

Social Support Services Needed

Ky Humble’s hometown is Afton, Okla., which had a inhabitants of about 800 when he was rising up. He belongs to the Cherokee Nation and was raised a Southern Baptist. He doesn’t bear in mind studying about HIV in any respect when he was in class.

“Even if I did, it clearly wasn’t enough,” Humble stated. “I knew I was gay in middle school; I think I would have paid attention.”

When he was identified with HIV six years in the past, at age 21, Humble felt as if his life was ending.

“I knew that that was a thing, [but] I was very ignorant,” he recalled. “I was two weeks away from graduating from college — you’re supposed to be on top of the world. I thought it was a death sentence.”

Ky Humble, who now lives in Oklahoma City, says there must be extra help for people who find themselves HIV-positive.

He referred to as his mother instantly. She instantly drove throughout the state to be with him.

“We just sat there and cried for six hours straight,” Humble stated. “And then we actually went [out] and bought several books on HIV, and just started reading them — to try to figure out what was going on.”

Today, Humble is wholesome. His HIV levels are undetectable and he will get common medical therapy to maintain it that approach. He now lives in Oklahoma City, however his household nonetheless lives in his hometown. He stated some individuals again in Afton know he has HIV, and a few don’t.

“It’s like coming out as diabetic,” Humble stated. “I don’t necessarily tell people that I’m HIV-positive. It’s just part of who I am; it doesn’t define me.”

He stated he’s cautiously optimistic that the Trump administration’s plan may imply extra funding for HIV prevention in Oklahoma. But rural Oklahomans, Humble stated, additionally want entry to “wraparound services” — equivalent to meals pantries, psychological well being remedy and transportation help — to assist them cope with the illness.

“I have friends who have HIV and live in rural areas, and just getting to appointments is challenging,” he stated.

Oklahoma’s Uninsured Rate Is Second-Highest In U.S.

Exactly how a lot cash the president’s HIV plan will get is as much as Congress. But even cheap, confirmed strategies for preventing HIV — like distributing condoms — is usually a robust promote in a state that doesn’t mandate complete intercourse schooling.

Informational HIV talks with youngsters typically flip right into a primary well being class for dispelling myths, stated Andy Moore, clinic administrator of the Infectious Diseases Institute on the University of Oklahoma.

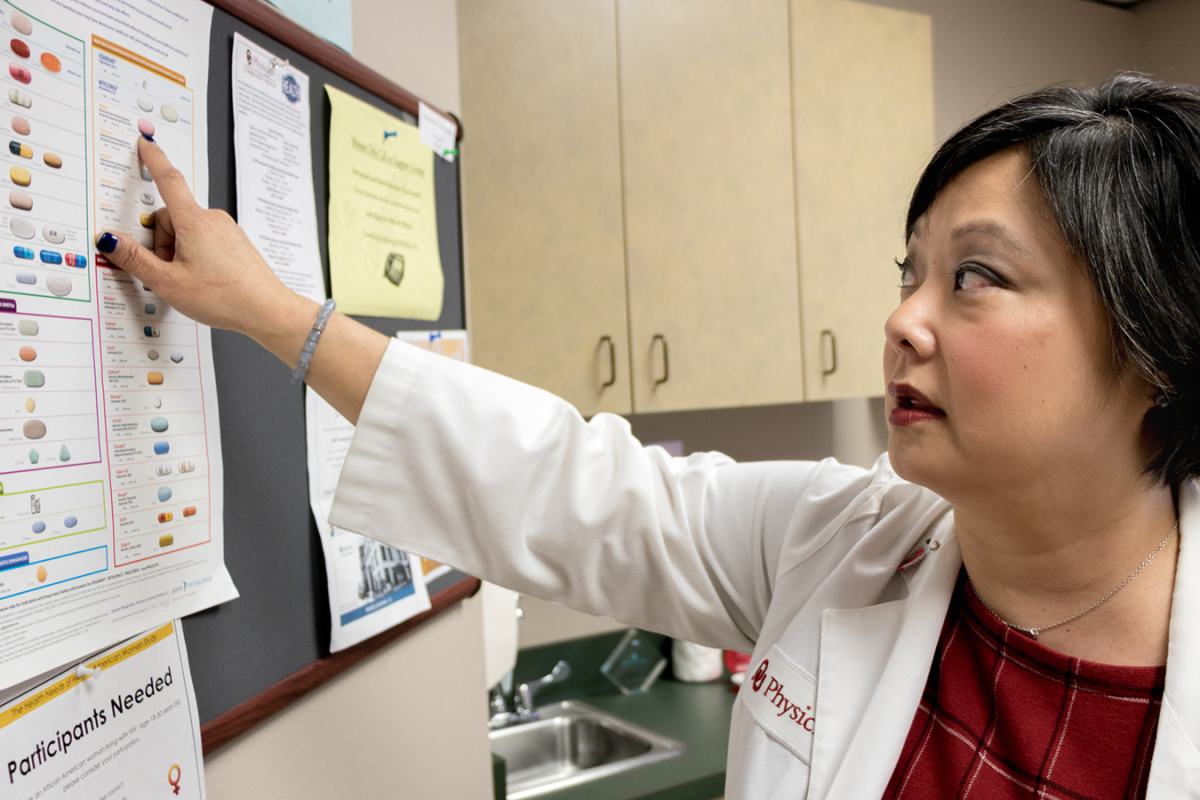

Salvaggio holds one of many medicines she prescribes to her sufferers with HIV.

“We’ve had teenagers write questions like ‘I’ve heard that if you douche with Mountain Dew after sex that it kills sperm,’” Moore stated. They earnestly wish to know if that’s true. “We have to back way up and explain what sex is, how babies are made, different types of sex — before we can teach them about HIV prevention,” he stated.

Another challenge in Oklahoma, Moore stated, is that individuals aren’t getting identified with HIV till they’re already sick due to AIDS, or near that time.

“Which indicates that they didn’t get tested until they had been living with the disease for six, eight, 10 years,” Moore stated. “We have one of the highest rates of late testing.”

Salvaggio stated 1000’s of individuals throughout Oklahoma would have to be examined for HIV to succeed in the administration’s purpose. And Oklahoma has the second-highest uninsured fee within the nation after Texas — that means many individuals don’t have a main care physician, not to mention prescription drug coverage for drugs like Truvada, which can be utilized to forestall HIV an infection.

It’s additionally one in every of 14 states that haven’t expanded Medicaid below the Affordable Care Act. So, even when extra individuals have been examined for HIV, getting those that want it into therapy wouldn’t be straightforward, Salvaggio stated.

Health care in Oklahoma is underfunded, she stated, and couldn’t deal with a sudden inflow of latest sufferers. “I don’t know what we’d do with all those new patients,” she stated. “We don’t have a facility to see them in, and we don’t have [the] providers.”

This story is a part of a partnership that features StateImpact Oklahoma, NPR and Kaiser Health News.