This story additionally ran on The World. This story could be republished free of charge (details).

Over the previous few months, medical professionals on Chicago’s South Side have been attempting a brand new tactic to deliver down the world’s toddler mortality fee: discover girls of childbearing age and ask them about all the things.

Really, all the things.

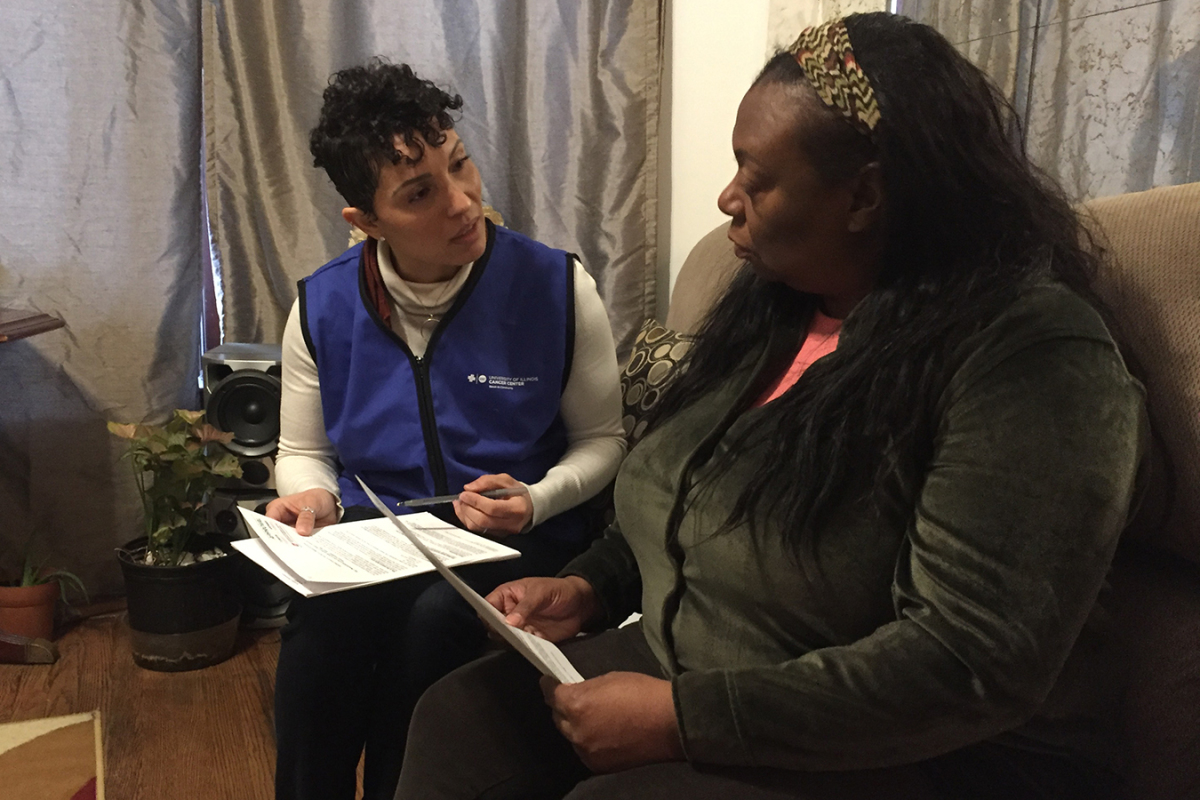

“In the last 12 months, have you had any problems with any bug infestations, rodents or mold?” Dr. Kathy Tossas-Milligan, an epidemiologist, requested Yolanda Flowers throughout a latest go to to her dwelling, in Chicago’s Englewood neighborhood. “Have you ever had teeth removed or crowned because of a cavity?”

Though they appear to have little to do with motherhood, these questions are borrowed from the playbook of the Chicagoans’ new mentors — medical doctors from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health. As Tossas-Milligan administered her survey, two Cuban medical doctors sat close by, observing.

Cuba, a poor country the place most of the automobiles on the street are half a century outdated, could seem an unlikely position mannequin for American well being care. But its toddler mortality fee, at four.three per 1,000, is decrease than the United States’ 5.7 per 1,000, in line with the World Health Organization’s 2015 knowledge. And Cuba’s fee is a lot better than the toddler mortality charges in some of the poorest parts of the U.S. In the Englewood neighborhood, as an illustration, 14.5 infants per 1,000 don’t attain their 1st birthday. That’s a fee akin to war-torn Syria.

Dr. Jose Armando Arronte-Villamarin, a physician from the Cuban Ministry of Public Health, observes Yolanda Flowers’ interview with Dr. Tossas-Milligan. (Miles Bryan/WBEZ)

“Cuba is not a rich country,” mentioned Dr. Jose Armando Arronte-Villamarin, one of many Cuban medical doctors. “[So] we have to develop the human resources, at the primary health care level.”

Now University of Illinois at Chicago well being employees are bringing Cuban-style surveys and residential visits to Englewood.

“Sometimes the answers are in the most unexpected places,” Tossas-Milligan mentioned. “Sometimes it’s hard for us to face the reality that, as much as we spend, we have somehow not been successful at keeping our babies alive.”

The dwelling visits got here out of a partnership between the Cuban Ministry of Public Health and the University of Illinois Cancer Center. Three Cuban medical doctors and a nurse embedded in Chicago from August to December, becoming a member of their American counterparts in visiting the properties of 50 girls of reproductive age in Englewood.

In trade for a $50 stipend, the ladies reply dozens of questions, on subjects starting from the state of their dwelling to their emotional well-being.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

The mission is funded by a $1 million grant from the W.Okay. Kellogg Foundation, which has additionally paid for some American well being care employees to go to Cuba.

In Chicago, researchers plan to make use of the info they collect to categorise girls into 4 threat teams. Those deemed at larger threat might be beneficial for added dwelling visits. The thought, Tossas-Milligan mentioned, is to handle these girls’s medical points at an early stage and at dwelling as a lot as potential, to keep away from expensive hospital payments.

“What we are hoping to discover is issues in Englewood that truly impact health, that are not being collected,” she mentioned, “that the doctors cannot see when they come and see [a] woman, and prescribe her one pill.”

One query the staff has been asking girls for instance, is once they final noticed a dentist. Gum illness, whereas unlikely to come back up throughout an expectant mom’s hospital go to, has been linked to premature birth.

In her interview, Yolanda Flowers mentioned that she hadn’t been to a dentist “since 1999 or 2000,” which she attributed to an absence of insurance coverage and a longtime concern of the dentist. And at 47, Flowers has had a tough obstetric historical past: three miscarriages and one untimely start. Her child didn’t survive.

Yolanda Flowers has had a tough obstetric historical past: three miscarriages and one untimely child who didn’t survive. (Miles Bryan/WBEZ)

Flowers, who mentioned she had “bare-bones insurance” or had been on Medicaid for a lot of her grownup life, first tried a deliberate being pregnant in 2003, together with her then-fiancé. She visited a physician who, Flowers recalled, suspected an ovarian cyst. But earlier than they went additional, Flowers’ fiancé died in an accident. In 2009, she tried to get pregnant once more and visited a distinct physician for assist. That physician, supplied beneath a distinct medical insurance plan, was not conscious of her historical past, Flowers mentioned, “because you only get a limited amount of time with the doctors, and there is only so much that I remembered.”

Tossas-Milligan and Arronte-Villamarin mentioned that even when Flowers doesn’t try one other being pregnant, merely having that data, and having it in a single place, might assist them head off issues dealing with different potential moms within the neighborhood.

The American well being care employees wish to scale up this method to handle different key well being issues in underserved components of the town.

Experts who’ve studied the Cuban well being system say that’s an thought price exploring, however it will require far more than simply dwelling visits and well being surveys.

“When a doctor or team [in Cuba] finds there problems in the home … and they think it has any bearing on her pregnancy, she gets help,” mentioned Dr. Mary Anne Mercer, a senior lecturer emeritus on the University of Washington.

Mercer famous that Cuba, regardless of being very poor, ensures sources for at-risk girls.

By distinction, the Chicago effort might establish girls in Englewood as needing meals or totally different housing, however they must discover a method to fill these wants on their very own.

“Thinking about a very poor, low-income, disadvantaged setting in the U.S., I don’t think we’ve got those resources,” Mercer mentioned. “So it’s nice to say, ‘Yeah, we could do it, if we were willing to expend those resources,’ but I am not convinced we could.”

“Would,” Mercer corrected. “I’m not convinced we would.”

This story is a part of partnership with WBEZ and PRI’s The World.

KHN’s protection of those subjects is supported by Heising-Simons Foundation and The David and Lucile Packard Foundation

Miles Bryan, WBEZ: @miles__bryan

Related Topics Public Health Children’s Health Women’s Health src=”http://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js” charset=”utf-8″>