Use Our Content This story may be republished free of charge (details).

FRESNO, Calif. — On the 15-mile drive between his two Central Valley medical clinics, Dr. J. Luis Bautista usually passes armies of farmworkers stooped over within the fields, selecting onions, melons and tomatoes.

Most of the 30,000 annual workplace visits to his small workers of docs and nurses in downtown Fresno and the close by rural city of Sanger are by these farmworkers. Many of them are undocumented.

The 64-year-old doctor has private perception into the struggles of those laborers: He was as soon as certainly one of them. As a boy, he picked fruit alongside his mother and father and 9 siblings in Ventura County. The household made $four,000 a 12 months again then, somewhat over $30,000 in at the moment’s dollars — hardly ever sufficient to spare for physician’s visits.

These days, Bautista sees that many farmworkers nonetheless lack the transportation, cash or time without work from work to deal with accidents, not to mention search preventive medical care. Plus, there may be the heightened worry that by looking for medical remedy they may be uncovered to federal immigration authorities.

“I pledged in medical school to help these people in the farm fields,” stated Bautista. “I knew how it felt not to have anything, not to have the money to go to a doctor.”

Now he treats them whether or not or not they’ve cash — or authorized paperwork. “We never say no to patients,” he stated.

President Donald Trump’s marketing campaign pledge to deport an estimated 11 million immigrants who’ve entered the U.S. illegally has fostered worry amongst farmworkers nationwide. Terrified they’ll be caught in an immigration dragnet, farm laborers throughout the San Joaquin Valley with out U.S. citizenship or official paperwork keep away from driving to see a health care provider or go to an emergency room.

Email Sign-Up

Subscribe to KHN’s free Morning Briefing.

Although California law strictly limits the state’s cooperation with U.S. immigration enforcement, some jurisdictions exterior the Central Valley have determined to take part in federal efforts to detain undocumented employees. Many right here worry that native officers will quickly be part of them, Bautista stated.

Farmworkers additionally fear that non-public data housed in docs’ workplaces may discover its manner into the arms of federal authorities. And some worry that in the event that they enroll in applications for low-income residents, they’ll later be denied everlasting residence, the so-called inexperienced card, or U.S. citizenship.

The Trump administration has proposed a federal rule change that may make it tougher for authorized immigrants to get inexperienced playing cards if they’ve obtained sure public help advantages, together with meals stamps, housing subsidies and Medicaid — the government-funded well being care program for folks with low incomes.

“Many people don’t know what the government will do,” Bautista stated. “They tell me that one reason they don’t go to the doctor is over fear they’ll be reported.”

Bautista’s two clinics present a haven for immigrants burdened by these considerations. Patients are by no means requested about their immigration standing, and the staffs have arrange protocols in case the workplaces are raided by immigration authorities.

“I feel secure with him,” stated Julia Rojas, a 45-year-old undocumented mom of 5 who has picked oranges in Fresno County for 20 years. “He’s one of us.”

Bautista accepts as cost no matter his sufferers can supply: onions, handmade key chains, eggs, even dwell chickens.

Dan Baradat, a Fresno private damage lawyer who has dealt with circumstances involving migrant employees, stated Bautista’s clinics are indispensable to the Central Valley’s poorer residents. “They’re stand-up people who provide care to people who could not otherwise afford it,” he stated.

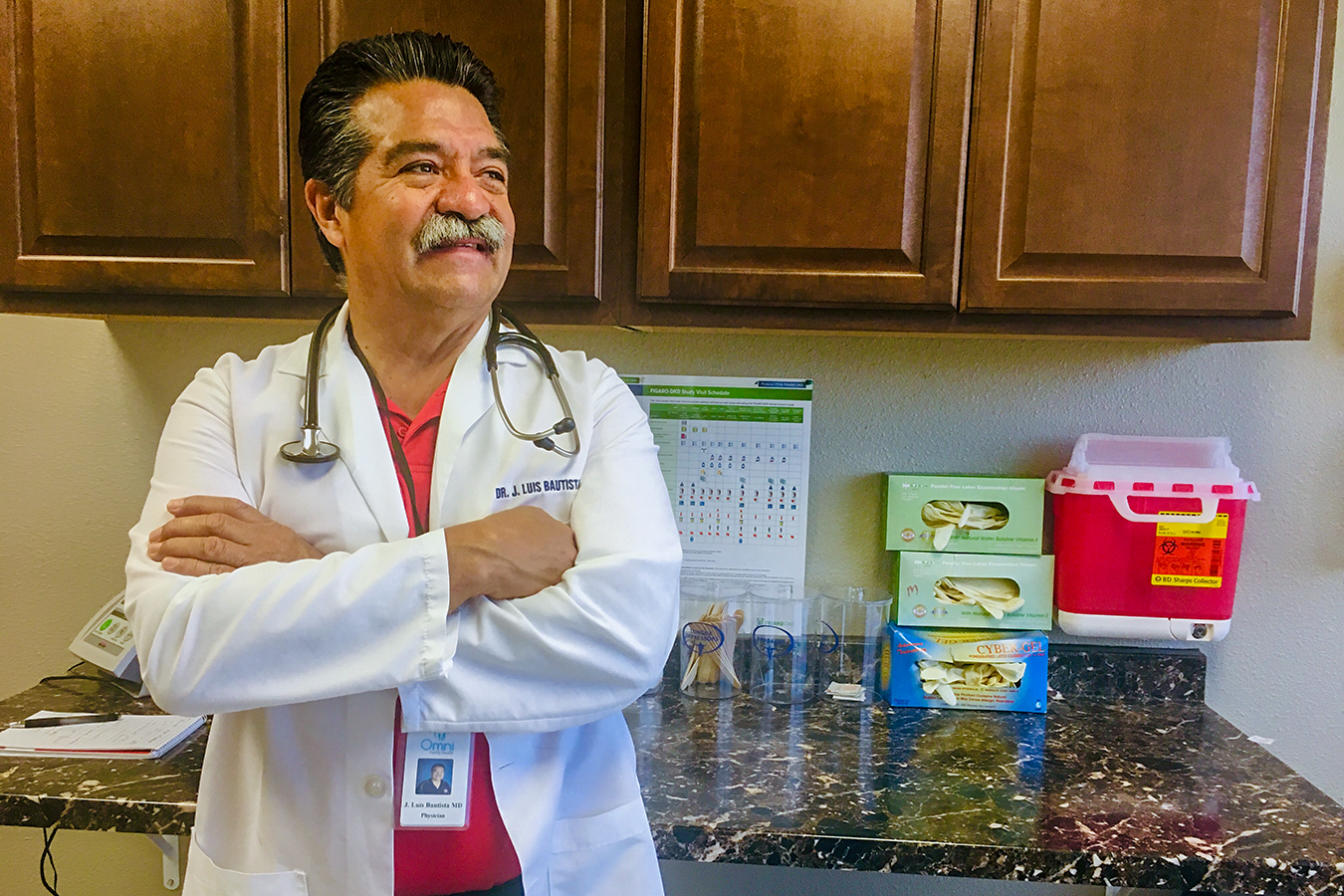

Bautista, a former farmworker, runs two clinics in California’s Central Valley offering care — usually freed from cost — for migrants who don’t have cash and are deeply frightened concerning the federal authorities’s hard-line stance on immigration. (John M. Glionna for KHN)

Bautista’s clinics are amongst a community of federally supported neighborhood clinics that present take care of almost 1 million migratory and seasonal agricultural employees and their households across the U.S. But few suppliers have a greater connection to the neighborhood they serve than Bautista, who in 2013 based a nonprofit that raises cash to help low-income farm households with meals and clothes, and gives scholarships to ship their kids to varsity.

Born in Fresno, Bautista was deported along with his mother and father when he was simply three months outdated. He lived in Mazatlán, Mexico, till he returned to the U.S. at age 12.

In 1979, at age 24, he was selecting lemons when his mom got here operating out to the fields with the letter asserting he’d been admitted to medical faculty. She’d all the time been large on training for her 10 kids.

Bautista attended the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee and did his residency in inner drugs on the University of Nevada-Reno.

Today, Bautista’s two sons are additionally docs, as is his son-in-law, who was a farmworker earlier than attending medical faculty and has joined the clinic. They all know that worry of deportation is affecting farmworkers’ well being.

Dr. Ed Zuroweste, founding medical director of the nationwide Migrant Clinicians Network, stated a current survey of suppliers throughout the group underlined these fears.

“What we’re seeing on the front lines is that farmworkers and their families are not coming in for regular appointments as frequently as they had before,” he stated.

Bautista stated many undocumented farmworkers depend on house cures to deal with illnesses resembling diabetes and hypertension, usually till it’s too late for efficient medical remedy. “By the time I see many diabetic patients, their feet are already necrotic and we have to amputate,” Bautista stated. “It’s terrible to see.”

Jose Jimenez, a former farmworker, stated his father, who just isn’t on this nation legally, was too afraid to drive to Bautista’s workplace, even after creating indicators of melanoma on his face. His dad’s fears have been heightened final 12 months following the death of an undocumented couple, the mother and father of six kids, whose van overturned whereas they have been fleeing federal immigration officers in close by Delano.

“He was even afraid to drive to the supermarket,” stated Jimenez, 30. “He knew that if he was picked up, he’d be deported. For a close-knit family like ours, that would mean losing everything.” But Jimenez lastly persuaded his father to go to Bautista.

Bautista’s clinics are on guard towards U.S. immigration officers, identified on this neighborhood as la migra.

Law enforcement officers requesting data are requested for a warrant, and workers members are looking out for intruders. “By the time any ICE officers got inside the office,” Bautista stated, “we’d have people hiding in the restrooms.”

Julia Rojas stated her fears of deportation virtually killed her. Years in the past, earlier than she started seeing Bautista, she selected to disregard the piercing ache in her decrease stomach. In the U.S. with out papers and afraid to drive, she spent almost a day ingesting mint leaves in scorching water — a treatment her mom used for abdomen ache again in Mexico.

Unable to face the spasms, she lastly went to the closest emergency room, the place docs eliminated her gall bladder. “Among undocumented workers in the fields, we have a dark little joke,” Rojas stated. “You can survive out here. Just don’t get sick.”

Use Our Content This story may be republished free of charge (details).

This KHN story first printed on California Healthline, a service of the California Health Care Foundation.

Related Topics California Public Health Doctors Immigrants Trump Administration